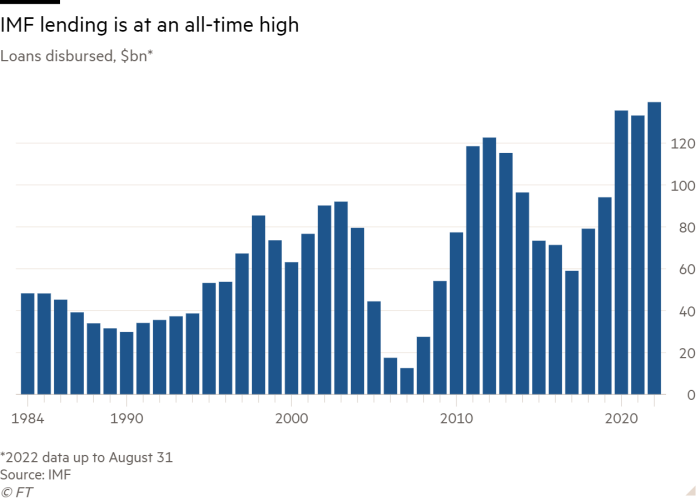

The IMF’s lending to economically troubled countries has reached an all-time high as the world’s lender of last resort faces simultaneous crises that have left at least five countries in default, with more expected to follow.

The pandemic, the Russian attack on Ukraine and a sharp rise in global interest rates have forced dozens of countries to seek IMF help. An analysis of IMF data by the Financial Times shows that the volume of loans disbursed by the fund at the end of August was $140 billion in 44 separate programs.

The figure, which is expected to grow further in the coming months as borrowing costs rise, is already higher than the outstanding loan amount at the end of 2020 and 2021, when the level reached all-year highs.

Experts predict that further large rate hikes by major market central banks will drive up borrowing costs around the world and threaten to trigger a severe recession. Some analysts say the IMF’s borrowing capacity could soon be stretched to its limits as poor countries without access to the international debt market must turn to the fund for support.

The IMF’s total commitments, including loans agreed but not yet disbursed, already exceed $268 billion.

Kevin Gallagher of Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center warned that “only so many countries” could get IMF support without “breaking the IMF balance sheet.”

Gallagher is co-author of a report this week warned that 55 of the world’s poorest countries could face debt servicing of $436 billion between 2022 and 2028, with about $61 billion due this year and in 2023, and nearly $70 billion by 2024.

The fund downplayed the concerns. The total pledges are “still a fraction of the” [almost] $1 trillion that could be available,” said Bikas Joshi, division chief of the IMF’s strategy, policy and assessment division. “The amount of loans is increasing in line with the increased risks countries are turning to us for support.”

The IMF is negotiating with several countries support packages that would further increase its overall commitments.

Zambia and Sri Lanka — both of which defaulted during the pandemic, along with Lebanon, Russia and Suriname — are negotiating bailouts from the IMF as part of efforts to restructure their debts. Ghana, Egypt and Tunisia are in talks about similar support.

The IMF approved a $1.1 billion bailout for Pakistan in late August; Argentina will receive $3.9 billion in the coming weeks as part of its $41 billion program.

Under IMF rules, member states can usually only receive aid equal to up to 145 percent of their IMF quota or shareholding, roughly equivalent to each country’s share of the global economy.

This would leave $370 billion available to low- and middle-income countries, in addition to the IMF’s approximately $940 billion in total borrowing capacity.

But that limit is often crossed. Argentina’s bailout package — which was approved in March as a debt restructuring of the record $50 billion in 2018 IMF bailouts — is equal to more than 10 times its quota. Analysts at Goldman Sachs expect Egypt to receive a $15 billion package soon, equivalent to nearly six times its quota.

The IMF is expanding its borrowing capacity to a limited extent. It traditionally borrows from two main facilities, the so-called general resource account and the poverty alleviation and growth trust, which lends at lower interest rates to low-income countries.

It recently established a Resilience and Sustainability Trust intended to help countries deal with systemic challenges such as climate change, which Joshi said had received funding commitments worth $40 billion, against a target of $45 billion.

A new food shock window, to help countries hit by rising food costs, is likely to be approved by the IMF’s board of directors ahead of its annual meetings next month.