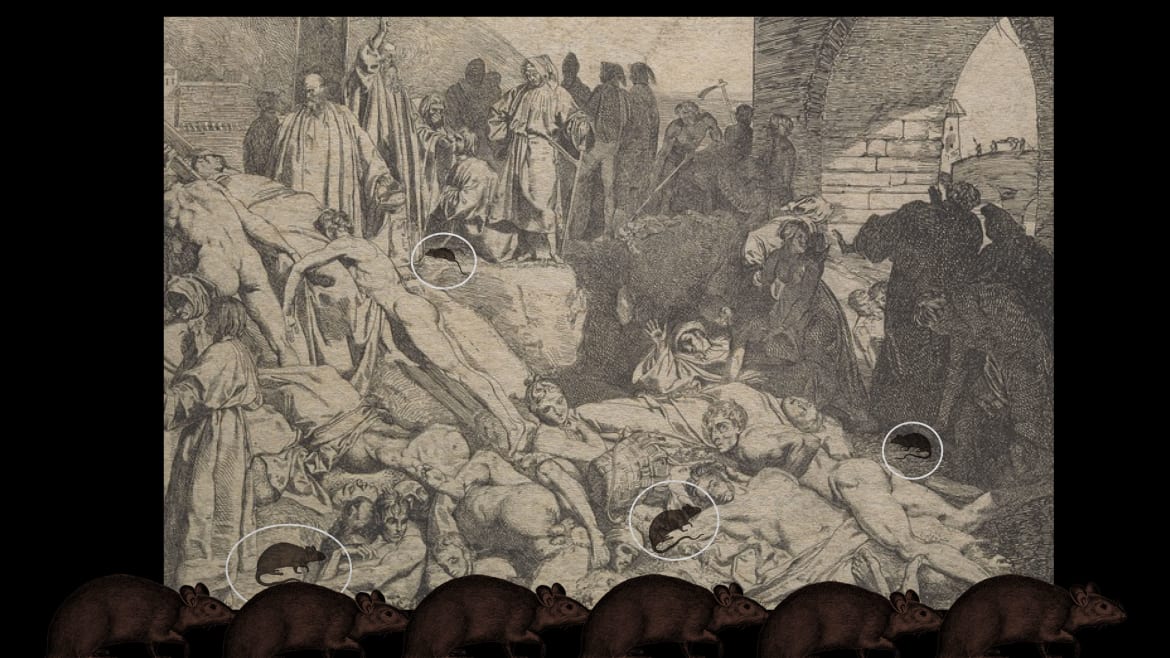

Photo Illustration by Erin O’Flynn/The Daily Beast/Wellcome Images/Wikimedia Commons

There is a legend that you may have heard about the arrival of the Black Death to Europe. According to a story told by Italian notary Gabriele De’ Mussi, plague arrived in 1346, when ‘Tartars’ attacking the city of Caffa in the Crimea came down with a mysterious illness. The dying Mongols decide to catapult the bodies of their dead over the walls of the city to infect the inhabitants within. That illness was bubonic plague. From there, the story goes, the plague spread throughout Europe, killing somewhere between 30-50 percent of the population.

While the impact of the Black Death in the fourteenth century is undeniable, this does not mean that the narrative about how or when it began is accurate. New research that fuses paleogenetics, historical detective work, ecological studies, and biology is challenging what scientists and historians thought they knew about the plague with some important consequences. As it turns out, the plague that ravaged Europe in the 14th century began much earlier than thought. The culprit wasn’t Mongols’ biological weapons (there’s no other evidence that they weaponized corpses), it was something much smaller…and cuter.

While scholars have been interested in plagues for a while and interest in historical pandemics heated up as we encountered coronavirus, there are only a few people who can deftly navigate both the historical and scientific material. At the forefront of this interdisciplinary effort is Dr. Monica Green, an award-winning medieval historian whose work interrogates narratives about plague. She gathers up all the available forms of evidence and insists that whatever narratives we tell have to be anthropologically, biologically, and historically plausible.