Netflix

For all his flights of fancy, Wes Anderson has always been a meticulously efficient filmmaker in terms of both style and substance, and The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar (in theaters Sept. 20 and hitting Netflix on Sept. 27) is his most cleverly concise—as well as arguably his most thrilling—work to date. A 39-minute version of Roald Dahl’s 1977 story of the same name, and the first of four planned Dahl shorts he’s directing (this after he already helmed 2009’s stop-motion Fantastic Mr. Fox), the auteur’s latest takes a uniquely faithful approach to adaptation, even as it remains an electrifying act of cinematic showmanship. A beautiful and bountiful bite-size film, it stands as Anderson’s second triumph of 2023 (following June’s Asteroid City) and a mini-masterwork in its own right.

Anderson doesn’t merely channel Dahl’s prose in The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar—he reproduces it, having various individuals pull double duty as characters and narrators. Speaking directly to the camera to recite third-person commentary and, also, their own dialogue, Anderson’s protagonists are all storytellers, and thus their tale becomes, in a certain sense, a celebration of storytelling. That notion is underscored by the self-consciousness of the entire endeavor, be it various figures breaking the fourth wall, diverse sets materializing and disappearing as if they were on a stage, animated backgrounds providing scenery for driving and outdoor walking sequences, or crew people literally adjusting actors around the frame as if they were mannequins.

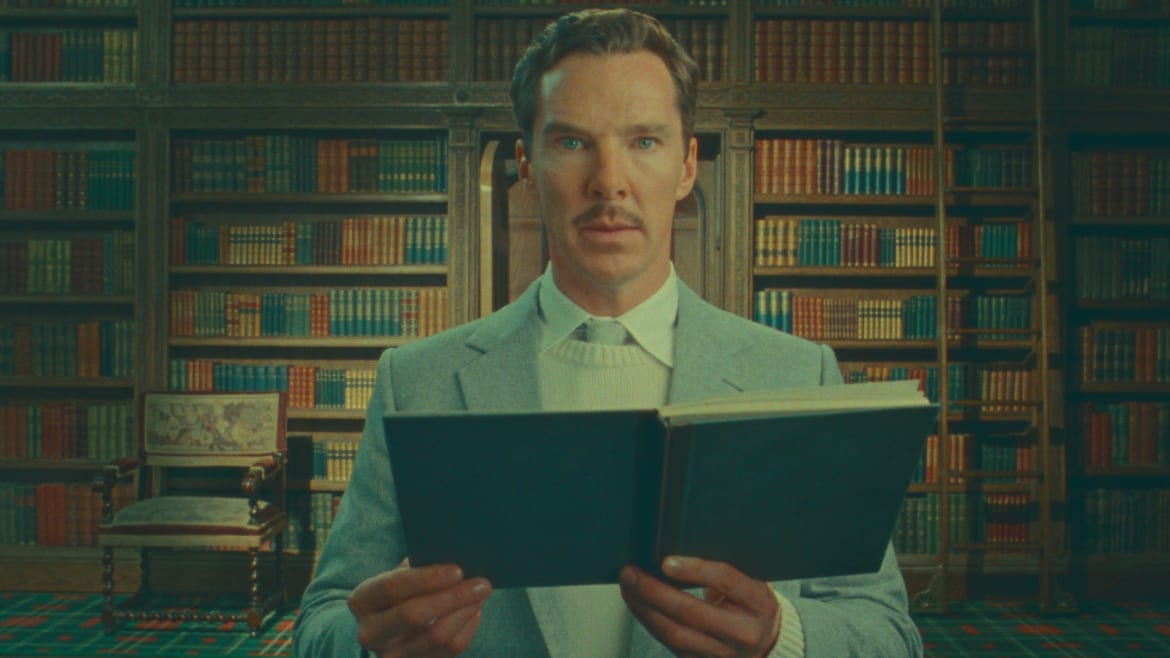

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar revels in artifice because it’s about the wondrousness of fiction—even though its narrative is posited as a true story, save for the name of its main character. That would be Henry Sugar (Benedict Cumberbatch), who’s first described by Dahl himself (Ralph Fiennes) from a favorite chair in his study, its walls lined with pages and drawings and its nearby surfaces adorned with telephones and other knickknacks. Dahl explains that Henry is a 41-year-old whose wealth comes from his father (rather than his own toil) and whose bachelorhood is a result of his selfishness. He is, Dahl says, neither a good or bad man but “simply part of the decoration,” and as Dahl’s office gives way to the exterior of his Gipsy House and then to a regal mansion, he cedes the literal and verbal spotlight to Henry, who details the true origins of his extraordinary saga.