The acquisition of bipedalism is considered to be a decisive step in human evolution. Nevertheless, there is no consensus on its modalities and age, notably due to the lack of fossil remains. A research team, involving researchers from the CNRS, the University of Poitiers and their Chadian partners, examined three limb bones from the oldest human representative currently identified, Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Published in Nature on August 24, 2022, this study reinforces the idea of bipedalism being acquired very early in our history, at a time still associated with the ability to move on four limbs in trees.

At 7 million years old, Sahelanthropus tchadensis is considered the oldest representative species of humanity. Its description dates back to 2001 when the Franco-Chadian Paleoanthropological Mission (MPFT) discovered the remains of several individuals at Toros-Menalla in the Djurab Desert (Chad), including a very well-preserved cranium. This cranium, and in particular the orientation and anterior position of the occipital foramen where the vertebral column is inserted, indicates a mode of locomotion on two legs, suggesting that it was capable of bipedalism.

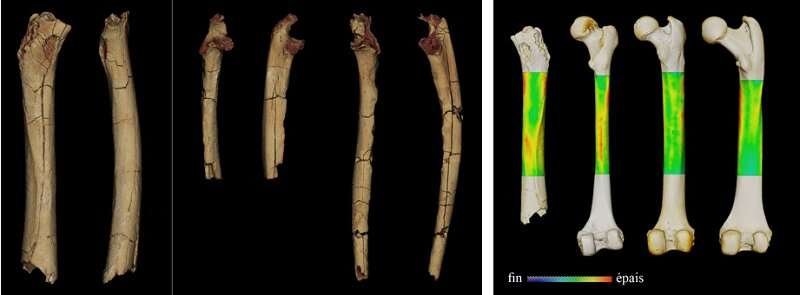

In addition to the cranium, nicknamed Toumaï, and fragments of jaws and teeth that have already been published, the locality of Toros-Menalla 266 (TM 266) yielded two ulnae (forearm bone) and a femur (thigh bone). These bones were also attributed to Sahelanthropus because no other large primate was found at the site; however, it is impossible to know if they belong to the same individual as the cranium. Paleontologists from the University of Poitiers, the CNRS, the University of N’Djamena and the National Center of Research for Development (CNRD, Chad) published their complete analysis in Nature on August 24, 2022.